I’ll never forget the first time I realized my father’s love for me might be conditional. I was a junior at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, and I had just come out as gay to him over the phone.

In a perfect world, my dad would’ve told me he loved me no matter who I loved and, maybe more naively, I hoped that he would tell me that being gay was OK.

Unfortunately, neither of those things happened. To say that my father, an ordained Baptist minister, didn’t take the news well is an understatement. He called me incessantly every day thereafter from our Brooklyn family home to read me scriptures on what the Bible says about homosexuality.

READ MORE: Billy Porter speaks up for Black LGBTQ: ‘Our lives matter too’

When he learned that I was dating a man in Atlanta, he gave me an impossible ultimatum: end my relationship with my then-boyfriend and essentially become a born again, straight man all with the snap of a finger (if only it was that simple). And if I didn’t, my father said, he would cut me off financially.

“Let whoever you’re with take care of you,” he said. He called it tough love.

It was incredibly heartbreaking and terrifying to make sense of my dad’s rejection and, at just 19, the possibility of being on my own and supporting myself took me to places of sadness and fear that was both familiar and uncharted. On one end I was concerned about my livelihood. Would I have to drop out of college? Would I ever be able to take care of myself?

And on the other end, I internalized my father’s rejection of what was technically only a part of me (my sexuality), and yet somehow it felt like he had rejected all of me. I had played out many scenarios in my head of how my father would react the day I’d finally tell him my truth.

As I’m sure many Black LGBTQ children can relate to, my greatest fear was to become another queer youth kicked out of the nest and left to fend for themselves in an already cruel and scary world where being anything but white and straight felt like a death sentence in America.

Sadly, twelve years after my coming out story, only 12 percent of Black lesbian, gay, bisexual and queer youth are out to their parents, according to a 2019 study by the Human Rights Campaign.

And those brave enough to come out are often faced with not only the rejection but homelessness. What’s more, as is pointed out by The Trevor Project, “being Black in the United States has its own unique experiences coupled with its own specific challenges, and very little is known about how to address the needs of Black LGBTQ youth. Research has documented a variety of challenges faced by Black youth, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety.”

As an act of survival, I chose to stand down. I went against what was in my heart, which was to fully step into my authentic self for the very first time in my life, and instead, I begrudgingly made the decision to go back inside the closet. It was safer that way.

I continued to be the model son that my dad knew me to be. I excelled in my academics, pursued an early career in campus journalism, and whenever a family member made an awkward comment about whether or not I was dating anyone, I’d mysteriously smile and chuckle without saying a word like the rehearsed closeted gay man I was.

READ MORE: J. August Richards on coming out as gay on Instagram: ‘I told my truth’

I wish I could say that there’s a happy ending; that eventually my father came around and accepted me as gay. But the truth is my father died two years later and we never got the chance to resolve what would ultimately become an unspoken wound in our relationship.

Anyone who identifies as gay, bisexual, trans, or queer can relate to the loneliness that comes with knowing who you are and not being able to share that fullness and authenticity with the ones you love most. My father died before he got the chance to know the fullness of who his son was. He also died before seeing who his son would ultimately become.

That reality is deeply painful. It’s for that very reason why Father’s Day is always a difficult day for me. Not just because of who I lost, but what I lost: the chance to be fully seen, loved and accepted as I am by the man who both created and nurtured me.

In many ways, I feel robbed of an opportunity to heal my somewhat broken relationship with my father. It’s a very complicated love story that has led me to nearly two years of therapy (and counting) to unpack the seen and unseen traumas of being a Black queer boy reared in a Black, conservative Christian household.

To be clear, I grew up in a beautiful and loving home. My father and mother were married for nearly 30 years before he passed, and my parents, who worked city jobs in New York City, did everything in their power to give me and my autistic brother the best that life had to offer. My father sacrificed his body and ultimately his health as he worked overtime nearly every day as an MTA transit worker to get me through private school and eventually college.

In fact, he rarely ever stopped working. Until, of course, he came down with what was thought to be a cold but was actually congestive heart failure. It would ultimately take his life just days after he turned 60.

My father’s death, and by extension Father’s Day, bring up complicated feelings for me. I was blessed enough to have a father who was active in my life, in fact, I felt at times he was a bit too involved. He knew my semester schedule by heart and would call me in between classes to talk about nothing at all. Something that once felt smothering is the very thing I yearn to have just one more time.

I’d be lying if I said that I was completely healed from the loss of my father and the chance for him to accept me, but I find comfort in knowing that the love we shared was real, no matter how messy and complicated it may have been.

The truth is I’m still reconciling with the fact that I’ll never get to experience my father’s acceptance. He’ll never get to say sorry for the pain he caused me, and I’ll never get the chance to forgive him for it. But while some things were left unsaid, in my heart I believe my dad would’ve come around to accept his gay son.

In the two months of being back home from college, my dad and I began to bond on another level, not just as father and son, but as two individual men. He was just starting to finally see me as my own person. It became less about what he wanted for my life and more about his curiosity for what I wanted for my life and where it was headed.

The night before he died, my father came into my room for what would be our very last conversation together. I was soon to begin my graduate studies at Columbia University, and he was very excited that his son was attending an Ivy League.

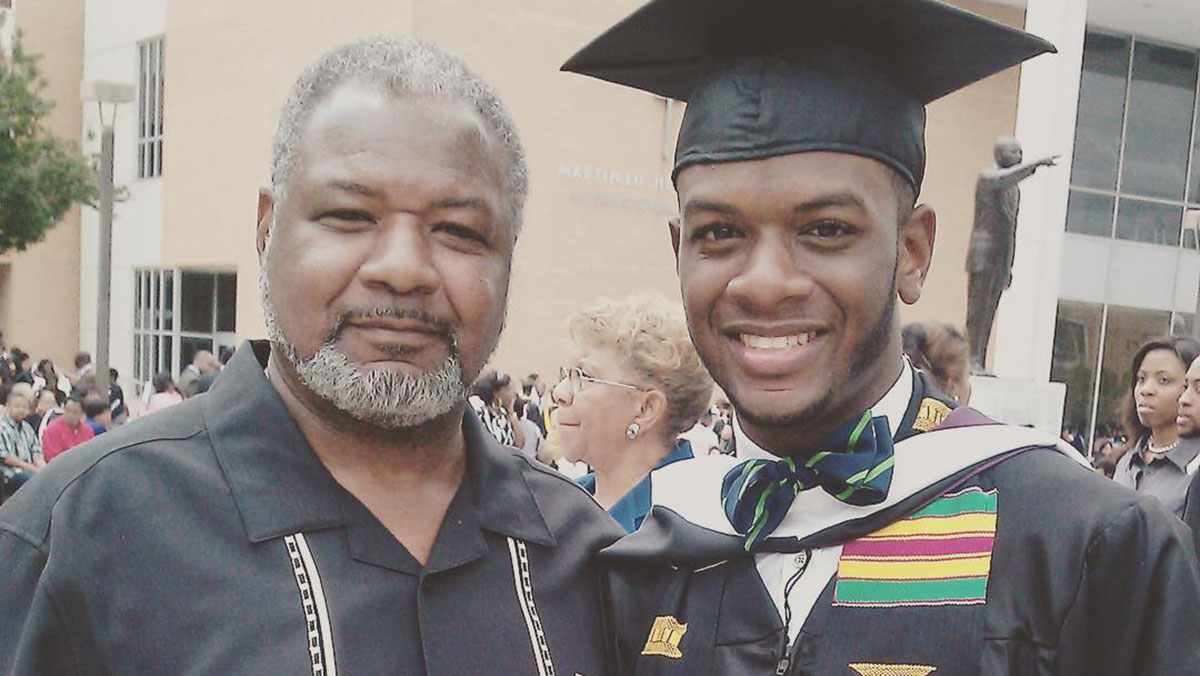

“What do you hope this will do for your career?” he asked me. As I laid out my 10-year plan, I remember him smiling as his face beamed with pride. It was the same pride on his face when I graduated from Morehouse. Seeing his Black son, a first-generation college graduate, accomplish what he and his ancestors never had the privilege of doing was deeply gratifying for him.

In fact, aside from the day he dropped me off on campus, my graduation was the only time I ever saw my father cry. I can still see the love enveloped in his tears as I looked him in his eyes before he embraced me.

“You make me so proud,” he said during that final late-night chat in my room. “Seeing you graduate was the happiest day of my life after the birth of my four children.”

Looking back on it, there was nothing conditional about my father’s love. And while he never explicitly accepted me as gay, he didn’t have to. I know now that there was nothing that would’ve stopped my father from loving me.

My relationship with my dad may have been complex but it was never absent of love. I hold on to that love on this Father’s Day, reminded that while he may no longer be with me in the physical sense, his loving spirit remains and comforts me when I need him most.

Gerren Keith Gaynor is the Managing Editor at theGrio and co-host of the Dear Culture Podcast. The Brooklyn native is a graduate of Morehouse College and Columbia School of Journalism. Previously, he served as an editor at Fox News, BET and Vibe magazine. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter @MrGerrenalist.

Gerren Keith Gaynor is the Managing Editor at theGrio and co-host of the Dear Culture Podcast. The Brooklyn native is a graduate of Morehouse College and Columbia School of Journalism. Previously, he served as an editor at Fox News, BET and Vibe magazine. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter @MrGerrenalist.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s new podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now!

The post Remembering my father who died before he could accept his gay son appeared first on TheGrio.

from TheGrio https://ift.tt/3fIMYC9

via